.It’s a funny thing about holidays in the country, but after only a few days away you feel as if you’ve been out of circulation for a month…

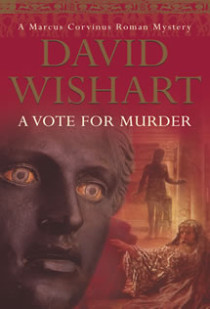

Marcus Corvinus is already restless after a couple of days in the Alban Hills, visiting his stepdaughter, Marilla; a regular seat in Pontius’s wineshop is all very well but bucolic leisure has its limits. So when he is asked to investigate the brutal slaying of Vettius Bolanus, one of the two candidates for the forthcoming censor’s elections, he jumps at the chance.

Corvinus feels sure there is a political motive for the murder, and the obvious suspect is Concordius, the rival candidate. But as he pursues his investigations, the obvious solution becomes less and less likely. Can Corvinus find his murderer before the Latin Festival raises the stakes? How do the Latin Nationalists fit into the picture? And what exactly is Meton the chef up to with Dassa the sheep? Marcus Corvinus doesn’t know the answers, either.

White Murder - Chapter 1

There’re worse places to hole up in when the poetry klatsch takes over the living-room and your wife throws you out for the duration than Renatius’s wineshop on Iugarius. The wine’s good for a start, a cheap, no-nonsense, swigging Umbrian that he brings in direct from the family farm near Spoletium but which could’ve walked all the way to Rome by itself. Then there’s the seedy, spit-and-sawdust ambience and matching clientele, which is a definite plus for the area. With Market Square and the Senate House just up the road, Iugarius wineshops – and there’re several, all with classy modern-style frescos and Gallic beechwood furniture – are packed in the late afternoon with jolly, back-slapping broad-stripers and pushy young business execs. If you haven’t experienced the joy of these guys yourself, then believe me: the last thing you want when you’re relaxing over a jug is a loud-voiced pack of the world’s élite at the next table swigging overpriced Falernian, calling the consuls by their first names and swapping hilarious anecotes about leaky aqueducts and building tenders. Renatius’s punters are tunics, which means most of the buggers have chins, speak through their mouths and would stand comparison with an intellectually-challenged parrot.

So. There I was, killing time in Renatius’s wineshop until Perilla’s poetry pals had finished juggling their anapaests or whatever the hell they do at their literary meetings and it was safe to go home. I was halfway down the jug with a plate of sheep’s cheese on the side and getting pleasantly stewed when the mystery man turned up.

You don’t see royalty much in Rome, not in Renatius’s, anyway, but if he’d been a prince of the blood from one of the eastern client-kingdoms slumming it incognito he couldn’t’ve created a bigger stir; which was interesting because like I say Renatius’s is definitely tunic country and these guys don’t impress easy. Yet the moment he walked in the door you could’ve heard an olive bounce, and Renatius himself moved so fast to show him to a table that he blurred. That was weird, too: you’d expect it in an upmarket cookshop, but any wineshop I’ve ever been in you find your own table, and if there isn’t one free then tough. Added to which the last time I’d seen Renatius move that fast was when a stray dog wandered in and cocked its leg against the counter, and as far as I could see there was no difference between this guy and the other half-dozen punters currently soaking up the booze.

I poured myself another slug of Spoletian and inspected him over the top of my cup. It was none of my business, sure, but I couldn’t help wondering what kind of semi-divine being we’d got here. Scratch the prince of the blood theory. Whoever he was, the guy was no easterner, let alone royal (I’d’ve guessed southern Italian, and if he rated more than a plain mantle I’d eat my boots); Renatius wouldn’t stir himself for any common-or-garden noble, home-grown or imported; and I’d bet a gold piece to a meatball that none of his clientele would recognise a visiting scion of the Commagene royal house if it leaned over and bit them. So where did that leave us?

Early thirties, lad-about-town type: sharp haircut, good quality tunic and enough flashy personal jewellery to fit out an Aventine cat-house. He was no Market Square patsy, though, that was sure; there were muscles under that tunic, the arm that lifted the wine jug had tendons you could use for catapult cable, and I’d hate to face those hard, cold eyes across the table in a needle dice game. All that plus the fact that the whole room bar me obviously knew him and was treating him like one of the Sacred Shields of Mars while he acted like he expected nothing less could only mean one thing. Or one of two things, rather. Our mystery pal was either a top swordsman or a ditto driver; either of which qualifications, as far as the punters in Renatius’s were concerned, put him less than one step down from Jupiter himself.

Personally, I’d go for the second option. Gladiators tend to be tall, even the lighter netmen: netman or not, quick on your feet or not, you don’t last long on the sand if you’re a short-arse with stubby legs and no reach; not when you’re matched against two hundred pounds of mean beefsteak armed to the teeth and anxious to check out the colour of your liver. This guy was a runt. A steel-and-whiplash runt, sure, but if he clocked in at any more than five-two and ninety-eight pounds then I was a blue-rinsed Briton. Which, of course, was perfect for the cars because the less there is of the driver the more chance the team has of romping home clear of the competition.

Me, I don’t follow the Colours. Yeah, I can keep my end up in a barbershop conversation, and Perilla and I go to the races now and again at the bigger festivals, but I’m no fan. Fans’re something else, and every tunic is a fan born. Renatius’s clientele mightn’t be in the league of the weirdos who paint every room in their house green or blue and sniff the favourite’s droppings before the race to check that it’s in prime running condition, but the tunic who doesn’t know his way around the teams well enough to play spot the hero when he walks into the local wineshop just don’t exist. So I sat back and watched developments.

Not that there were any at first. Renatius’s kid son Lucius brought the man his jug and a plate of olives, setting them down like they were honey-cakes on a shrine, and Mystery Boy was left to his own majestic thoughts while everyone else went into huddles and muttered away quietly. Every so often the guy glanced towards the door like he was expecting someone, but if so his pal wasn’t showing.

Ten, fifteen minutes in, he stood up suddenly and beckoned to Lucius. Conversation in the room switched off like it would in the local temple if the cult statue decided to stretch its legs in the middle of the ceremony, but Mystery Boy didn’t seem to notice. Probably he was used to it and it didn’t bother him any more, one way or the other.

The kid went over like he was walking on eggs. He had to swallow twice before he got his voice to work.

‘Yes, sir?’ he said.

‘Where’s the privy?’

I could see the blush spread over the kid’s face from freckle to freckle: obviously in Lucius’s personal world demigods didn’t ask questions to do with normal human functions. Besides, Renatius’s is pretty basic; the guy might just as well have asked for directions to the bath suite. I grinned and sipped my wine.

‘Uh…I’m sorry, sir.’ Swallow. ‘We, uh, we haven’t got one.’

‘You haven’t got one.’ Mystery Boy didn’t smile, but one of the regulars, a little wizened monkey of a guy called Sestus with plaster stains down his tunic, sniggered into his winecup. ‘So where do your customers piss?’

‘Uh…’ Lucius was beginning to look desperate. ‘In the alley, sir. Round the side. There’s a wall at the end. You can’t miss it.’

Sestus choked on his wine. Mystery Boy ignored him. He nodded to Lucius and went out, closing the wineshop door behind him.

The place erupted like a schoolroom when the master pops out for a breath of sanity.

‘You can’t miss it, right, Lucius?’ Sestus said when he’d finished coughing his lungs out. ‘Not on less than two jugs, anyway.’

‘Nice one, lad.’ That was Renatius.

If the kid had been blushing before, now you could’ve used his ears to signal ships. Understandable: he’d just had his chance to impress the great man with his witty repartee and he’d blown it all over the shop. Being ten is tough.

‘Hey, Lucius,’ I said. ‘Who is the celebrity, by the way?’

Lucius’s jaw dropped. There were a couple more laughs, at me this time. ‘But that’s Pegasus, sir!’ he said.

Tone like he was speaking to an idiot, which in the race-mad kid’s eyes I suppose I was. Yeah, well, I’d got that one right, at any rate. The guy was a driver; or not just a driver but one of the drivers, currently. Even I knew Pegasus: half the plaster statuettes on sale outside the Circus had his name on them. Not that that would’ve been any help with the face, mind, because they all came out of the same mould, whoever they were supposed to be, and the names were written on later; but the name itself, that was a different thing altogether. ‘The Greens’ lead?’

‘Not any more, sir. He’s driving for the Whites now. Or at least he will be when the new season starts.’

‘Is that right?’ I sat back while the kid mopped the table. Now that was something you didn’t hear of every day, a Green high-flyer transferring to the Whites. Blues I could’ve understood, because as far as professional street cred’s concerned the Blues and the Greens are pretty well on a par. Whites and Reds are definitely the poor relations. Sure, transfers among the factions go on all the time, and it’s common enough for a second-rater on the Blue or Green team to make the switch to White or Red just so’s his name comes higher on the programme, but for one of their top-notch drivers to do the same is like a Praetorian moving to the Watch. Worse, the guy hadn’t just moved down a peg, he’d changed camps as well: on the track the Whites run point for the Blues just as the Reds do for the Greens. Still, I was no racing buff. No doubt it made sense somewhere along the line. I went back to my wine and cheese.

I wasn’t the only silent drinker now. For the next ten minutes the whole room held its communal breath and kept one eye on the door, waiting for the guy to reappear. He didn’t. Finally Sestus cleared his throat. ‘Maybe he’s missed the wall at that,’ he said.

His mates chuckled. Renatius was rinsing cups at the sink. He didn’t turn round. ‘Come off it, Sestus,’ he grunted. ‘Joke’s over.’

‘You want me to check on him, Dad?’ Lucius was hopping with excitement. ‘Just to see if he’s all right?’

Renatius shrugged and reached for a towel. Lucius dashed off. We waited.

The kid hadn’t been gone two minutes when he was back. He didn’t come in, though.

‘Uh…dad?’ He was chalk-white. The hairs rose at the nape of my neck.

‘Yeah?’ Renatius said over his shoulder. ‘Close that door, boy, there’s a draught.’

‘Dad, I, uh, think he’s dead.’

It took a moment to register. Then Renatius dropped the towel and was through the door in five seconds flat; and the rest of the wineshop, including me, were about two seconds behind him.

Dead was right.

The guy was slumped face-forward against the end wall of the alleyway. On the back of his tunic, just level with the heart, was a broad red stain.

There was one of these horrible pauses while we all tried to persuade ourselves that we weren’t seeing what we were seeing. Renatius shook his head.

‘Oh, shit,’ he murmured. ‘Oh, holy Jupiter.’

The other punters crowding the narrow alley said nothing. Even Sestus had shut up.

Bugger. Well, someone had to make a move. ‘Renatius, get everyone back inside, okay?’ I said. ‘Then you stand guard at the mouth of the alley to make sure no one comes barging in. Oh, and send Lucius to the local Watch station.’

‘Waste of time, consul,’ Sestus murmured without taking his eyes off the body. ‘The commander’s Titus Valgius. The guy’s a total prat.’

I ignored him. ‘Just do it, Renatius.’

The big man nodded. He was looking grey. ‘Come on, lads,’ he said. ‘Show’s over.’

No one moved; ogle, ogle, ogle. I sighed. Hell: I’d seen this before, and I hated it. Give the great Roman public a corpse or an accident to stare at and they’ll stand there all day. There was only one answer: expensive, sure, but it’d save a lot of hassle in the long run. And where Renatius’s regulars were concerned it’d work every time. ‘Fine,’ I said. ‘Drinks are on me. At the counter, for the next five minutes only.’

‘You’re a gent, Corvinus.’ Sestus beamed. ‘Possessed of true leadership qualities.’

Oh, Jupiter! ‘Just fuck off, Sestus, okay?’

‘Certainly, sir. Fucking off at once, sir.’ He did, and the other ghouls followed him.

Which just left me and the corpse.