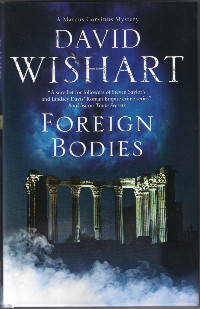

June, AD42. The emperor Claudius himself has requested Corvinus’s help in investigating the murder of a Gallic wine merchant, stabbed to death as he was taking an afternoon nap in his summer-house at Lugdunum.

Not especially happy at being despatched to Gaul, and even less enamoured of his enforced travelling companion, the insufferable Domitius Crinas, Corvinus is increasingly frustrated as it becomes clear that the dead man’s extended family and friends are hiding something from him. Unused to strange Gallic customs and facing an uphill struggle getting anyone to talk freely to a Roman, Corvinus is convinced that there’s more to this murder than meets the eye – but, a stranger in a strange land, how is he going to prove it…?

Foreign Bodies - Chapter 1

The end of June can be pretty hot in Rome; plus, of course, at that time of year when old Father Tiber is stripped down to his metaphorical vest and underpants and there’s more mud to him at the edges than water the low-lying bits of the city are fairly unpleasant, odour-wise; which is why most people who can manage it up sticks and head for cooler and more salubrious parts. Me, I’m OK with the heat, and so long as you remember to breathe through your mouth when circumstances demand walking around is just this side of bearable. Perilla, now…well, on top of the temperature and olfactory aspects of big city life the lady’s always been the more outgoing member of the partnership, and between July and September when things begin to settle down again society’s thin on the ground. A good time, then, for touching base with the family – adopted daughter Marilla, her husband Clarus and the grand-sprog, young Marcus – at Castrimoenium in the Alban Hills.

So that’s where we were off to bright and early the next morning, with all the arrangements made barring the finer details of the packing. That’s definitely Perilla’s department; me, while it’s happening I tend to lounge around on the atrium couch with half a jug of wine and let the lady and Bathyllus, our major-domo, get on with things between them.

Which is what I was doing when Bathyllus himself oozed in to say that a slave had arrived with a message.

‘Is that so, now?’ I said. ‘Who from?’

‘The emperor, sir.’

Wine splashed, and I sat up straight. ‘You what?’

‘A personal request.’ Bathyllus’s nose had a distinctly elevated tilt to it, and it had nothing to do with the drains: our major-domo is the snob’s snob. ‘He would be grateful if you could drop by some time today, at your earliest opportunity.’

Uh-oh; this did not sound good. Oh, sure, Claudius was a different kettle of fish altogether to his predecessor – at least, unlike Loopy Gaius of not-so-fond memory, he had a full set of tiles on his roof (so far, anyway; give it time) and he was likeable enough in his own right – but impromptu invitations for a cosy imperial tète-á-tète weren’t exactly a regular occurrence in the Corvinus household. Not that I was complaining, mind; where mixing with the buggers at the top is concerned, I’ve always found that keeping your head well and truly below the parapet is the best way to make sure it stays attached to your neck.

I set the now-empty wine cup down, reached for a napkin, and mopped my wrist. ‘He mention what it was about, at all?’ I said.

‘No, sir. But I imagine, from the wording of the message, that it is a matter of some urgency. I’ll fetch your best mantle, shall I?’

‘Yeah. Yeah, you do that.’ I hate those things, particularly in the summer months when wearing one is like walking through a steam bath wrapped in a sixteen-foot barber’s towel, but turning up at the palace in a lounging-tunic wasn’t an option.

Bathyllus exited, leaving me frowning: ‘a personal request’ and ‘at your earliest opportunity’ definitely boded. In spades. Still, I couldn’t very well tell the most powerful guy in the world to take a hike, now, could I?

Damn.

I stood up, just as Perilla came through from the direction of the stairs.

‘I’m sorry, dear,’ she said, ‘but if you were planning to take that old tunic you laid out on the bed with us you can think again. I’ve already thrown it out twice, and –’ She paused. ‘What’s the matter?’

I told her. To give her her due, under the circumstances, the lady was distinctly unfazed; but then like I say Perilla’s the social animal in the household, and if she and Tiberius Claudius Caesar weren’t exactly long-standing bosom chums they’d at least had a nodding literary acquaintance before his elevation, and a summons to the palace didn’t have the effect on her that it would’ve had when Gaius was running things. Nowhere near. Puzzlement, at best. Plus, given that we were practically en route to the Alban Hills, the barest smidgeon of annoyance.

‘But what can he possibly want?’ she said.

Bathyllus was back with the mantle. ‘Search me,’ I said, as he helped me on with it. ‘We’ll just have to wait and see. How do I look?’ I gathered up the last yard or so over my left arm in the obligatory fold. ‘Presentable?’

She regarded me critically. ‘More or less.’

Grudging as hell. ‘Come on!’ I said. ‘It’s the best I’ve got. You gave me it yourself at the Winter Festival, and it’s never been worn.’

‘True, Marcus. But then it never ceases to amaze me how even in a new mantle you still manage to appear slightly disreputable.’

I grinned. ‘Call it a knack.’

‘Then it’s one that you should not be particularly proud of. All right; make that “louche”, if you prefer. You’ll need the litter as well, of course.’

Bugger: swanning around in litters is another activity I can gladly do without. Still, she was absolutely right: turning up at the palace soaked with sweat and the accumulated mud and grime of a walk half way across Rome wasn’t an option. And at least the wine stain on the tunic was now decently hidden. I was just lucky she hadn’t spotted that and had me change completely.

‘Fair enough,’ I said.

She came over and kissed me. ‘Have a nice time,’ she said. ‘And give my regards to Tiberius Claudius.’

I sent Bathyllus to roust out the litter guys.

At least I couldn’t complain about being kept waiting. Under the new regime – well, Claudius had been emperor for a year and a half now, so maybe ‘new’ was pushing it a bit – the imperial admin system had gained an extra layer of unsightly fat, and arranging an appointment involved filling out forms in triplicate and smarming your way past an endless succession of snooty freedman clerks. Okay if you’ve got a few days to spare for twiddling your thumbs in antechambers, but frustrating as hell otherwise. However, right from the point that I gave my name to the hefty Praetorian on the door it was obvious that I was being given the full five-star VIP fast-lane treatment. The clerk detailed to look after me led me straight through the public offices, up the staircase to the private living quarters above and to the same richly-panelled door I’d been through eighteen months before, when I’d had my little chat with that bitch Messalina. I just hoped that she wasn’t in evidence this time around: cousin or not, emperor’s wife or not, that was a lady I wanted nothing whatsoever to do with that didn’t involve a ten-foot barge pole and an insulated pair of gloves.

The clerk knocked, opened the door, and stepped aside. I went in.

The room had been refurnished since Gaius’s day. Cosy enough, sure, if your idea of cosiness is a functioning office with a no-nonsense desk and wall-to-wall book cubbies. Nice collection of bronzes, mind, and considering where I was they’d all be originals.

The man himself was sitting behind the desk, writing. The desk was piled with book-rolls, plus a wine jug and cups that looked like they were permanent fixtures. He looked up.

‘Ah, C-Corvinus! Delighted you could come so promptly,’ he said. ‘Have a seat, my dear fellow. I’ll be with you in just a moment. ’ Uh-huh; well, at least he sounded fairly affable, which was a good sign. Not that I felt particularly reassured, mind. The clerk who’d brought me bowed and went out, closing the door behind him. I pulled up a chair that was as old as the bronzes and probably just as expensive and sat down while he finished what he was doing and laid the pen aside. ‘You and your wife Rufia Perilla are well?’

‘Yes, Caesar,’ I said cautiously. ‘We’re both fine. Perilla sends her regards.’

‘That’s excellent. A cup of wine? It’s not too early for you?’

‘No. Not at all. That’d be great, thank you. ’ Damn right it would; I wasn’t going to pass up what would no doubt be the best imperial Caecuban. One of Claudius’s good points – or good in my view anyway – was that he liked a cup or three of wine as much as I did. Besides, I suspected that I was going to need it. ‘Thank you.’

He poured and filled his own cup to the brim. I took a sip. Nectar, pure nectar!

‘Now. To business. You’re w-wondering, no doubt, why I asked you to come and see me.’

‘Uh…yeah. Yes, sir, I am.’

‘Perfectly natural. I want you to look into a murder for me.’

Oh, bugger. Bugger, bugger, bugger!

‘Really?’ I said faintly.

‘You do still handle them, don’t you? As a hobby, I mean. Only I recall our mutual friend Marcus Vinicius mentioning it. The evening of my late nephew’s dinner party when you and Perilla shared our table, if you remember.’

Uh-huh; the one just before Gaius got himself chopped. I wasn’t likely to forget that little bean-feast in a hurry, was I?

‘Ah…yes,’ I said. ‘Yes, I do. Handle them, I mean.’ If that was the proper word for it. ‘On and off, as it were.’

‘That’s m-marvellous. Vinicius told me you did when I asked him, but it’s just as well to check up on these things.’

I took another mouthful of the Caecuban, said nothing, and tried to look eager.

‘It happened just under a month ago, in Lugdunum. The victim was a Gallic chappie by the name of Cabirus. Tiberius Claudius Cabirus.’ He took another large swallow of wine and topped up the cup. ‘His father had the citizenship from mine when he was governor there shortly before the D-Divine Augustus passed over.’

Maybe I’d misheard. At least, I hoped I had. ‘I’m sorry, Caesar,’ I said carefully. ‘You said “Lugdunum”, right?’

‘You know it? Charming place, quite delightful. Of course, I was born there, so I’m b-bound to be a little biased.’

‘That’d be, ah, Lugdunum in Gaul, yes?’

‘Naturally; where else would it be? Cabirus was one of the town’s leading citizens.’

Oh, hell.

‘So this would, like, involve me in actually going there?’ I said carefully. ‘To Lugdunum. Over in, ah, Gaul.’

‘Well, Corvinus, it might be a little difficult m-managing things otherwise, mightn’t it?’ He must’ve noticed the look on my face. ‘Oh, my dear fellow, do forgive me! I’m not a tyrant! If you’re b-busy at present with other things then you only have to say. I’ll understand completely.’

Yeah. Right. And I was Cleopatra’s grandmother.

Fuck.

‘Only it would be a great pity. A very great pity. Vinicius said you’d had p-plenty of experience in this sort of thing, and that you’d be absolutely perfect for the job.’

Did he, indeed? Fuck again. Double fuck; I was screwed. Thank you, Marcus bloody Vinicius. With knobs on.

‘Ah…no, Caesar,’ I said. ‘I’m not busy as such. We had been planning to go through to the Alban Hills tomorrow, but under the circumstances I expect that can wait.’ It would sodding well have to, wouldn’t it? Perilla would be absolutely thrilled when I told her. Even so, it served her right: Vinicius was her literary pal, not mine, and if he’d put Claudius on to me then it was only because Big Mouth had given him the information in the first place.

Claudius beamed. ‘Excellent! I’m m-most relieved that I can leave things in your capable hands. And if you’re already p-packed for travelling then it’s even more fortuitous. You can leave right away. Don’t worry about travel arrangements; they’re already taken care of.’

‘I beg your pardon?’

‘My dear chap, do credit me with a little consideration! I am the emperor, after all, and I do have some clout. There’s a g-government yacht berthed at Ostia, ready to leave whenever suits you. This time of year, you can be in Massilia inside of three days. And I’m giving you – wait a m-moment, it’s here somewhere.’ He rummaged about among the papers on his desk and came up with a small, tightly-fastened scroll. ‘Ah. Here we are. I’m giving you imperial procurator status for the duration, as my p-personal representative.’ He handed me the scroll. ‘All properly sealed and signed. I’ve already written to Gabinius, so he’ll be expecting you and he’ll p-probably already have done the needful at his end, but it’s as well to be sure. In any case, show that to any official in the three provinces, Roman or local, of any rank, and he’ll fall over himself to be helpful.’

‘Gabinius?’

‘Quintus Gabinius. The Lugdunensis governor. Solid chap, first-rate at his job. You’ll like him.’

Gods, we were moving in high society here, right enough: personal use of a government yacht and imperial procurator status, no less. Pressured into it or not, I couldn’t complain that I was being short-changed. Which raised an interesting question. I tucked the scroll into my mantle-fold.

‘Ah…if you don’t mind me asking, Caesar,’ I said, ‘why should you involve yourself here?’

‘I beg your pardon?’

‘Well, okay, presumably, given his name, this Claudius Cabirus was a client of your family, yes? A current one, I mean?’

‘Naturally.’

‘Still, for you to go to all this trouble just for a client he must’ve been special in some other kind of way, right?’

‘No.’ Claudius picked up a book-roll that had fallen off the desk. ‘No, not at all. As I said he was an important man locally – in fact, I understand he was to be officiating priest at the opening ceremony for this year’s Gallic Assembly – but he was of no great importance in the grand scheme of things. Certainly not political importance, if that’s what you mean. In fact he was a p-perfectly ordinary middle-class merchant. A wine shipper. Quite prosperous in Gallic terms, but not what we’d call particularly rich.’

‘Then I’m sorry, but I don’t understand your interest.’

‘Oh, the answer’s simple enough, my dear fellow. Call it a personal debt, if you like. A very long-standing one, in fact.’

‘“Debt”?’

‘Two years before I was born, his father saved mine from a very unpleasant death in what is now Treveran Augusta; which, incidentally, is where the family is from, originally. P-pulled him in the nick of time from in front of the horns of a dozen bulls that had escaped from the local slaughterhouse. Hence the personal debt aspect of things.’ He smiled. ‘If it hadn’t been for the Cabiri Rome would not now be experiencing the inestimable p-pleasure of having me for emperor. We – my mother, while she was alive, and myself – have kept a grateful eye on the family ever since.’

‘Fair enough.’ Well, it made a change to have an emperor who took his debts seriously. Inherited ones, what was more. ‘So. What can you tell me, sir? About the murder itself, I mean.’

‘Very little, I’m afraid. Only what Gabinius put in his report, which wasn’t much. He was killed at his home, as I said just short of a month ago. Stabbed through the heart while he was taking his after-lunch nap.’

‘He have a family?’

‘A wife – Diligenta, her name is – , two grown-up sons and a daughter.’

‘Any particular enemies?’

‘Not that I know of. Certainly Gabinius didn’t say, but then I w-wouldn’t have expected him to, not in an everyday official report. Nor indeed to go into things to that length, particularly just now with all the preparations for the British campaign. His mention of the death was more in the nature of a postscript than anything else.’

Yeah, fair enough. Provincial governors were busy men at the best of times, and although the guy probably wouldn’t be directly involved militarily with Claudius’s upcoming plans to expand the empire he’d have his share of the bread-and-butter side of things to see to. Major military campaigns involve a lot in the way of extra-to-the-norm supplies and equipment; it all has to come from somewhere, and finding that ‘somewhere’ is a governor’s job. Gabinius just wouldn’t have the time to spend on a simple murder, of an imperial protégé or not, nor would he have the staff to delegate, and Claudius would know it.

Hence, presumably, me. Ah, well. It made a change, anyway, and I’d never been west of Ostia. Plus if I was travelling as an emperor’s personal rep at least we’d be doing things in style; Perilla would enjoy the novelty. Which reminded me…

‘I can take my wife along, yes?’ I said.

‘Oh, my dear fellow, but of course you can! Take whoever you like, within reason. In fact, I was going to suggest it myself. Rufia Perilla will enjoy the trip immensely. Not a p-particularly interesting place, Gaul, outside the old Province, a bit rough-and-ready, but as I said Lugdunum is charming. Make sure you sample the local wine, too. Very respectable indeed, on its home ground, and I speak from experience.’

‘Yeah,’ I said. ‘Yes, I’ll definitely do that.’

‘Jolly good.’ Claudius beamed and picked up his pen. ‘Oh, I almost forgot. Nothing to do with your mission, but you’ll have a travelling companion. I thought that since everything will be laid on transport-wise as far as Lugdunum I might as well kill two birds with one stone.’

‘Oh?’ I said. ‘And who’s that?’

‘One of my own people, a doctor by the name of Lucius Domitius Crinas. I’m sending him to make a survey of the medicinal hot springs near the German border, with a view to developing them for the use of the legions stationed there. After you reach Lugdunum he’ll be carrying on to Moguntiacum where the Fourteenth Gemina and Fourteenth Gallica are based.’

Bugger! My son-in-law Clarus aside, doctors I can do without, particularly on long journeys like this would be. Still, the person making the arrangements being a ruling emperor, there wasn’t a lot I could do about it. And you never knew; like Clarus, the guy might buck the trend and turn out to be okay company. We’d have to wait and see.

It’d only be as far as Lugdunum, anyway.

Claudius reached for his writing tablet. ‘Well, that’s about it,’ he said. ‘There’s n-nothing more to be said, really. Certainly no more information I can give you. So unless you have any questions yourself – ’

I could recognise a polite dismissal when I heard one. I stood up.

‘Not at the moment,’ I said. ‘Thank you, Caesar.’

‘Oh, tush, tush! What for? You’re the one doing the favour, my dear chap. Thank you, and good luck to you. And of course you’ll tell me how things went when you get back. We’ll have you round to dinner, you and Perilla. A quiet family dinner, not one of those silly big affairs like the last time. Messalina will be delighted.’

Yeah, I’d just bet she would; skeleton at the feast wouldn’t be the half of it. And it wasn’t something I was particularly looking forward to, either. I said nothing.

He stretched out his hand, and I shook it.

‘Thank you again, Valerius Corvinus,’ he said. ‘Do give Perilla my very best regards. And have a p-pleasant and successful journey.’

I left.

So much for that. Now all I had to do was break the glad news to the lady that her holiday arrangements were shot to hell.